The Jeffersonian Roots of Today's Neocon Apocalypticism

Did the Radicalism of America's Most Famous Founder Help Sow the Seeds of Future Nuclear Apocalyse?

In the wake of the Biden administration’s recent escalatory moves in Ukraine, for the first time in decades, the threat of a genuine, all-out nuclear war is a real possibility. In fact, this may be the first time the world has been this close to a large-scale nuclear exchange since the early 1960s.

One wouldn’t know it, though, if one’s only source of information and opinion is mainstream news media, whose opinion pages are (when they bother to cover world events at all) dominated by neoconservative voices of varying political dispositions. And when it comes to the danger of nuclear brinkmanship between NATO and Russian leader Vladimir Putin, the verdict of these voices is clear and unanimous: we (the collective West) simply don’t care!

The argument tends to sound something like the following: Whatever meager power Russia (which, after all, is a decaying geopolitical corpse destined for the dustbin of history) is able to project abroad is purely the result of its doctrine of nuclear blackmail. A policy that has managed to stay the hand of the mighty U.S. military. A force that, if finally unshackled from its self-imposed slumber, could use its fleet of nigh-invincible stealth aircraft to blast through the Eurasian hordes and their rusting and outdated Soviet equipment in a matter of days, if not hours. This fact is a kind of historical injustice, preventing, as it does, the final and inevitable defeat of Russia and the forces of backward fundamentalist Christian tyranny and Asiatic despotism for which it stands and the final global victory of the forces of human freedom and liberty that the United States itself embodies.

Furthermore, Russian military corruption and incompetence (which is simply assumed) are such that most of their aging nuclear arsenal may not work at all, meaning that the U.S. could even potentially ‘win’ a nuclear exchange with Russia while suffering merely acceptable losses (getting one’s “hair mussed,” if you will).

That such appraisals are profoundly delusional doesn’t serve to lessen their narrative appeal for the vast majority of America’s ruling class of semi-literate urban professionals. Offering, as it does, an emotionally compelling backdrop upon which they can frame their own life’s story, which can illuminate it with the sense of greater meaning that it would otherwise lack. This allows the scattered, disconnected, brute events of one’s individual life inside the organized oblivion of modern America to be redeemed through its association with the broader “arc of history,” which, as all good devotees of the American religion know, inevitably bends toward justice.

However, this narrative, which is simultaneously both compelling and insane, is by no means merely a recent fad of Washington’s ‘woke’ outer party, nor can it be laid entirely at the feet of the neoconservatives (a group who have become a convenient scapegoat in recent years for any and all of the more pathological tendencies in recent American policy, foreign or otherwise).

The attacks on neoconservatives, while in many ways deserved, have the handicap of frequently being unfair, especially when launched by Trump-era conservatives. The latter of which has the bad habit of treating the neoconservative tendency as, at best, an aberration in American life or, at worst, as a kind of foreign pathogen spread by trotskyite Jews beginning in the 1960’s.

At their most honest, Trump’s ‘New Right’ will occasionally mention the role of early 20th century progressivism (Woodrow Wilson and Oliver Wendell Holmes are occasionally name-checked), but very little beyond this basic admission is ever really allowed. The modern conservative movement was founded, after all, on a kind of veneration bordering on worship of the American founders. A veneration that entailed the concoction of a series of profoundly dishonest hagiographies. Today’s conservatives have learned the secret of making effective rhetorical appeals to America’s millions of consumer citizens, which, as Gore Vidal observed in his novel Burr, consists in offering them “no inconvenient facts, no new information. If you really want the reader’s attention, you must flatter him. Make his prejudices your own. Tell him things he already knows. He will love your soundness.”

While it is certainly true that these stories have served the practical political interests of conservatives well, they have also prevented them from thinking clearly or deeply about the actual basis of the more destructive and apocalyptic tendencies of neoconservative thought.

Neoconservatives (at least in this regard) have frequently been more honest and internally consistent.

In 2008, Robert Kagan, perhaps the single most influential neoconservative of the past 30 years, wrote an impassioned essay entitled "Neocon Nation: Neoconservatism, c. 1776” in which he defended his project in the wake of the Iraq War, in the process pushing back against the idea that Neoconservatism was a recent import imposed upon the American people by crypto-trotskyite Jews.

Kagan then goes on to easily demolish this premise, reading off a long list of examples starting from before the first world war and stretching back to the founding itself. As Kagan remarks:

To all the founders, the United States was a “Hercules in a cradle,” powerful in a traditional sense and also in a special, moral sense, because its beliefs, which liberated human potential and made possible a transcendent greatness, would capture the imagination and the following of all humanity. These beliefs, enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, were neither exclusively Anglo-Saxon nor Burkean accretions of the centuries but, in Hamilton’s words, were “written, as with a sunbeam, in the whole volume of human nature by the hand of the divinity itself.” And these ideals would revolutionize the world. Hamilton, even in the 1790s, looked forward to the day when America would be powerful enough to assist peoples in the “gloomy regions of despotism” to rise up against the “tyrants” that oppressed them.

Kagan was, of course, completely correct in pointing this out, inconvenient as this may be for today’s paleocon influenced MAGA-conservatives to admit.

However, while the fact that the founders were radical enlightenment deists who used violent means to reach revolutionary ends is begrudgingly admitted (even though it is quite obvious) by most American liberals and conservatives, the actual extent of this disposition tends to be downplayed in the various hagiographies of the founders, frequently to the point of obscuring it completely.

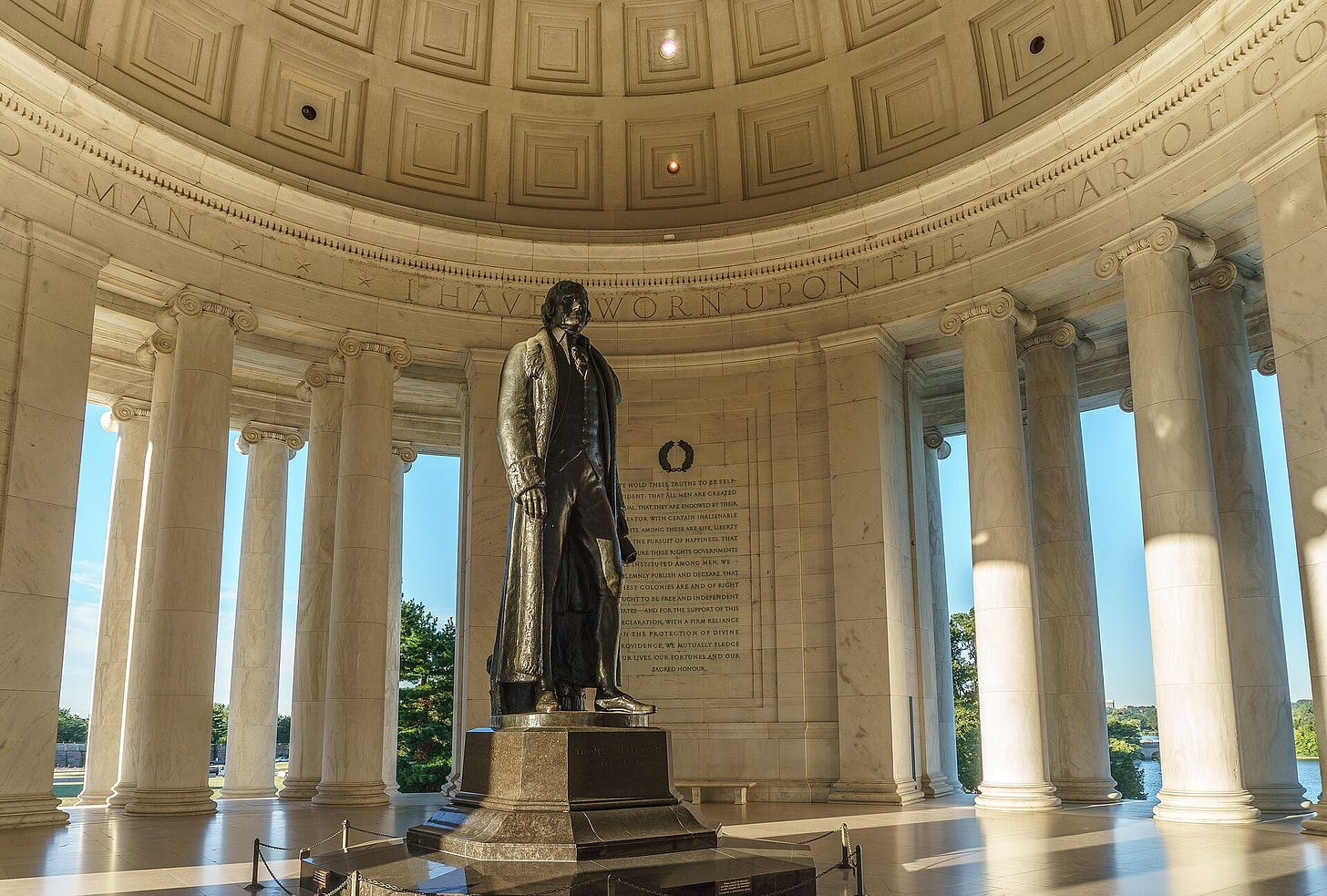

This is especially true when it comes to America’s arguably most important and influential founder: Thomas Jefferson.

Of course, Jefferson’s more famous ‘sins’ are relatively well known: his affair with Sally Hemmings, his spend-thrift tendencies, his embrace of slavery and profound contempt for blacks in general, his rejection of Christianity, his flirtations with the French Revolution, etc.

‘Flirtations’ being, at least how Jefferson’s connections to the French revolutionary project are generally described in the vast majority of the hagiographies, especially the conservative ones.

However, describing these descriptive tendencies as'misleading’ would itself be yet another mystification. In reality, such treatments are simply lies.

Jefferson’s record of embracing and promoting the profound violence of the French Revolution and his belief in the essential oneness of the Jacobin cause and his own is well documented, even if this has been largely suppressed or explained away in many American histories.

Though a great many other sources could be cited on this topic—enough to fill a book—the heart of what can only be fairly described as Jefferson’s apocalyptic insanity can be found in full in his infamous letter to his longtime secretary, William Short. A document that is worth quoting at length:

The tone of your letters had for some time given me pain, on account of the extreme warmth with which they censured the proceedings of the Jacobins of France. I considered that sect as the same with the Republican patriots, and the Feuillants as the Monarchical patriots, well known in the early part of the revolution, and but little distant in their views, both having in object the establishment of a free constitution, and differing only on the question whether their chief Executive should be hereditary or not…

In the struggle which was necessary, many guilty persons fell without the forms of trial, and with them some innocent. These I deplore as much as anybody, and shall deplore some of them to the day of my death. But I deplore them as I should have done had they fallen in battle. It was necessary to use the arm of the people, a machine not quite so blind as balls and bombs, but blind to a certain degree. A few of their cordial friends met at their hands the fate of enemies. But time and truth will rescue and embalm their memories, while their posterity will be enjoying that very liberty for which they would never have hesitated to offer up their lives. The liberty of the whole earth was depending on the issue of the contest, and was ever such a prize won with so little innocent blood? My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam and an Eve left in every country, and left free, it would be better than as it now is.

It is important to clarify just exactly what Jefferson is communicating in his passage: it is an explicit endorsement of extreme and demented revolutionary violence, including the murder of innocents (who Jefferson views as a kind of unfortunate, but likely unavoidable, collateral damage). It is also the recognition that there are potentially almost no limits to said violence (up to and including apocalyptic devastations of entire nations), provided the end result is ‘liberty.’

The obvious (if lazy) rejoinder to this by devotees of modern American civic mythology is simply to try and downplay it by attempting to reimagine it as a kind of off-the-cuff remark that should simply be ignored.

The problem with this, aside from it being a cowardly evasion, is that Jefferson made the remark not in a drunken stupor at a cocktail party but in an important diplomatic communique, one that shows no evidence of being thoughtlessly composed. Furthermore, Jefferson made the remarks, not as an impulsive young man nor as a bitter and senile old man, but when he was 49, at the height of his powers.

Furthermore, the violence in question was not merely an academic exercise for Jefferson; he had just spent years in France as U.S. ambassador and had witnessed the revolution firsthand. Perhaps most shockingly, he also knew many of the individuals who had become victims of the terror, including his personal friend Louis Alexandre de La Rochefoucauld, who had just been stoned to death by a revolutionary mob the previous fall.

Jefferson never meaningfully recanted any of the views he expressed to Short, though he would live for decades longer and was able to have a complete and unhindered view of the carnage engendered by his revolutionary allies in practice.

There are few American figures more influential than Jefferson; indeed, it would not be difficult to argue that he is, in fact, when all is said and done, the more important and influential figure of the American Founding.

Jefferson’s Declaration, with its soaring rhetoric and substance-free assertions, is perhaps the single most American document to ever be written. It is also easily the most important single document in American history, its words having been invoked at almost every major crisis in American history from the Civil War forward. After all, unlike the constitution, the declaration cannot be altered by amendments.

It’s also not hard to see the Jeffersonian influence on today’s (and yesterday’s) neoconservatives, as well as their ‘neoliberal’ cousins.

And it is certainly no mystery why this would be, as the logic of Jefferson’s own thought is elegantly simple (if also simple-minded): if ‘all men’ are indeed ‘endowed with certain inalienable rights’ and these rights are actually'self-evident’ to all reasoning men, then an obvious conclusion to make is that it is therefore the duty of all free men to aid those still in bondage. After all, as Jefferson’s letter to Short implies, there is a real sense in his own thought in which no one is really free until everyone is. And it is this idea that has driven much of America’s foreign policy down to today, with the subsequent corollary being that a life without maximal freedom is basically not worth living at all. The conclusion then being that the lives of the ‘unfree’ are expendable and that even the lives of the ‘free,’ those who Jefferson calls ‘innocent blood,’ are worth sacrificing if it significantly advances the cause of liberty, up to and past the point of apocalyptic, world-shattering violence if necessary. Ideas, which we can see consistently reflected in the actions of American foreign policy makers.

It is likewise unlikely that this tendency will be changed anytime soon, as the Jeffersonian outlook on the world is thoroughly ingrained in the popular American mythos and psyche. While there are, or at least were, alternative interpretations of the founding, these are long since extinct. Furthermore, none of these were especially appealing or viable, with the most prominent and interesting (though also among the most depraved) of the bunch: the ideas of John C. Calhoun, which would later serve as the bedrock of the short-lived confederate experiment, being essentially little more than the establishment of a brutal and depraved slave society along the lines of ancient Sparta.

Thus, the lust for apocalyptic violence shared by America’s leadership class is unlikely to be going away anytime soon, regardless of what figurehead happens to be inhabiting the White House at any given time. A fact that it is better to simply accept and discuss honestly regardless of how uncomfortable it may be to contemplate at first.

This is not a counsel of despair, nor is it a call to engage in foolish or, even worse, precious theorizing (nostalgia for monarchy, unreflective anti-Americanism, etc.), but rather merely an invitation to finally begin clear and honest thinking about the actual narratives that undergird the contemporary American lifeworld.

Simply put, Kagan and his ilk are largely right about the genealogy of their ideology and also about its future prospects. Accepting this reality is the first step in beginning to undo it, a mission that must inevitably fall either to us or to our progeny.

The latter of which, if we fail, may likely only number in single digits.

As Jefferson would have wanted.

Thanks for this thoughtful piece. This is similar to the argument that I make in my book, The Ideology of Democratism. I devote an entire chapter to Thomas Jefferson, whom I argue is an exponent of this kind of dangerous, revolutionary thinking (I quote that very letter to William Short) that has brought America to the point of constitutional crisis that it is at now.

So are you neocon adjacent? Your tortured reasoning is so insipid as it appears to have been written by a freshman in college trying to impress their TA.

Cherry picking from Hamilton and Jefferson (one letter!! 😳🙄😂) to argue that neoconservatism is as old as the Republic is an abject lie and an insult to the sociopaths who brought their poison to these shores. Further, relying on any of the Kagans’, proven serial liars, to make any point reveals a complete lack of common sense and critical thinking.

BTW, where are the Iraqi WMD?